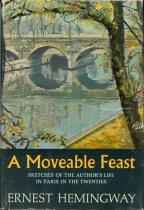

• A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

• Hardcover: 211 pages

• Publisher: Scribners, 1964 (first edition!)

• ISBN:64-15441

• Genre: Memoir/Classic

• Recommended For: Anyone interested in descriptive memoirs, classic authors, “the Lost Generation”, and writing tips from one of America’s best authors.

Quick Review:

An excellent quick read that inspires the aspiring writer and paints a lovely picture of Paris in the ’20s. Really brings Hemingway down-to-earth and makes me want to try to re-read some of his novels (never was a fan).

How I Got Here: My sister is currently on her belated honeymoon in Paris, and one of her goals was to see all the sights that she read about in this book. Before she left, she insisted that I also read the book, thinking that it would be inspiring as a writing book. This books satisfies tasks for A Classics Challenge, End of the World Challenge, and the Award-Winning Challenge. It’s also number 72 on my list for The Classics Club.

The Book: Goodreads’ Synopsis

“If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

– ERNEST HEMINGWAY, to a friend, 1950

Published posthumously in 1964, A Moveable Feast remains one of Ernest Hemingway’s most beloved works. It is his classic memoir of Paris in the 1920s, filled with irreverent portraits of other expatriate luminaries such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein; tender memories of his first wife, Hadley; and insightful recollections of his own early experiments with his craft. It is a literary feast, brilliantly evoking the exuberant mood of Paris after World War I and the youthful spirit, unbridled creativity, and unquenchable enthusiasm that Hemingway himself epitomized.

My Analysis and Critique:

I’ve written quite a bit about this book already, and I’m sure it’s obvious that I greatly enjoyed this book.

I was and am surprised that I enjoyed A Moveable Feast so much as I’ve never been a fan of Hemingway’s. I always considered myself in the Steinbeck camp–Hemingway’s style always felt cold to me. Maybe it’s his minimalist, lean style. However, A Moveable Feast was nothing but heart! I saw Paris through Hemingway’s eyes, I could hear every conversation he transcribed, and I could taste the delicious meals and wine he consumed.

The book is composed of the journal entries he recorded as a young man living in Paris in the ’20s, and this is apparent in his stream-of-consciousness style. It was very engaging. Hemingway reflects upon his favorite spots in the city, the start and dissolution of his friendship with Gertrude Stein, his true friends and his phony colleagues. He comes off as a jerk at times, but his writing reflects his youth, and is as forgivable as any youthful misbehavior.

A Moveable Feast is also full of writing tips from Hemingway, as he reflects quite a bit on his writing process, the obstacles that got in the way of his writing, and how he dealt with said obstacles. Any creative person would get something out of Hemingway’s tips. I would place this on the shelf next to my most-prized writing books.

Overall, I highly recommend this book for its wonderful descriptions of Paris, the lively characters that Hemingway reflects upon (including Stein, Ezra Pound, and F. Scott Fitzgerald), and the inspiration it stirs in my writer’s soul. A quick read and worth anyone’s time!

Check out my previous posts below to get a better feeling for the writing in the book!

Links:

A Moveable Feast and Paris in the ’20s

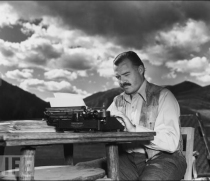

Classic Authors: They’re Just Like Us–Ernest Hemingway Part One and Two

We all know the legends of Ernest Hemingway–the drinking, the fishing, the safaris, the suicide. But, before Hemingway was known as “Papa”, he was “Hem”, and he was not that different from you and me.

We all know the legends of Ernest Hemingway–the drinking, the fishing, the safaris, the suicide. But, before Hemingway was known as “Papa”, he was “Hem”, and he was not that different from you and me.

Here are ten ways that Ernest Hemingway and other authors are remarkably similar to us!

Part One of this post can be found here.

1. They misplace their old journals!

2. They find writing to be “hard” and struggle with writer’s block.

3. They enjoy engaging in book talk with fellow readers!

4. They read fluff for enjoyment…but are wary of gambling with bad books.

5. They support indie authors!

6. They can’t afford books and hang out at the library.

7. They wish they could read their favorite books again for the first time.

8. They lose their luggage!

9. They put up with annoying people.

10. Their happiest times were when they were penniless.

*All information, quotes, and paraphrases derived from Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast, unless otherwise noted.

“In those days there was no money to buy books. I borrowed books from the rental library of Shakespeare and Company, which was the library and bookstore of Sylvia Beach,” (35)

Hemingway was a young, struggling author in Paris, but he loved to read and Beach’s bookstore served his reading needs more than adequately.

adequately.

“I was very shy when I first went into the bookshop and I did not have enough money on me to join the rental library. She told me I could pay the deposit any time I had the money and made me out a card and said I could take as many books as I wished.”

Hemingway immediately takes her up on the offer, grabbing six books, including Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler and Other Stories.

He frequented Shakespeare and Company often, where he had a friend in Beach, and could engage in conversation with other writers such as James Joyce and Ezra Pound. In addition, he received all of his mail at the library.

Sounds like the perfect library, right? Hang out in the back room and read any and all books you like, take as many as you want home with you, the proprietor is a sweetheart, literary discussion is encouraged, and you could pick up your mail! Where’s my local Shakespeare and Company?!

7. If I could turn back time…

Remember what it was like to read your favorite book for the first time? The wonder and excitement you felt? Don’t you wish you could do it all over again?  Hemingway and his pals did, and they mourned the loss of that reading experience.

Hemingway and his pals did, and they mourned the loss of that reading experience.

Here is Hemingway discussing with his poet friend Evan Shipman the re-readability factor of certain novels:

“[War and Peace] comes out as a hell of a novel, the greatest I suppose, and you can read it over and over.”

“I know,” I said. “But you can’t read Dostoyevsky over and over. I had Crime and Punishment on a trip when we ran out of books down at Schruns, and I couldn’t read it again when we had nothing to read[….]”

“Dostoyevsky was a shit, Hem,” Evan went on. “He was best on shits and saints. He makes wonderful saints. It’s a shame we can’t reread him.”

“I’m going to try The Brothers again. It was probably my fault.”

“You can read some of it again. Most of it. But then it will start to make you angry, no matter how great it is.”

“Well, we’re lucky to have had it read the first time and maybe there will be a better translation.”

“But don’t let it tempt you, Hem.”

“I won’t. I’m trying to do it so it will make it without you knowing it, and so the more you read it, the more there will be.” (137-138)

I wonder if these guys had ever tried my re-reading method: wait ten years until you’ve forgotten the details, then try it again. This usually works for me!

8. “It’s okay honey, don’t cry. At least I still have the carbons….YOU WHAT?!?”

En route to Geneva, traveling to reunite with her husband for the holidays, Hadley Richardson, Hemingway’s first wife, lost her suitcase.

No big deal. Just some clothes and toiletries, right? Wrong! Hadley traveled to Geneva with everything Hemingway had written in Paris so that he could work on them during their holidays in the mountains.

Again, no big deal, there were copies, right? Wrong! Hadley brought the originals AND the copies. “She had put in the originals, the typescripts and the carbons, all in manila folders,” (73).

Hemingway only had two stories left–one that had been rejected from a publisher and one that he had buried in a desk drawer because Gertrude Stein hadn’t liked it.

Hemingway was crushed, but brushed it off to his friends saying, “It was probably good for me to lose early work,” (74).

Literary scholars don’t think so. They are still hopeful that one day the suitcase will turn up.

Have you ever dealt with a hanger-on who won’t leave you alone and just won’t get the hint no matter how rude you are? Hemingway did, and he was so annoyed that he included an entire chapter covering this very hilarious incident. I related to it so much (although, I could never be as rude as Hemmingway was!) that I have read the chapter “Birth of a New School” a few times.

I’ve discussed this scene in a previous post, and I still think this guy reminds me of Kenny Bania, Jerry Seinfeld’s annoying fellow comic, on Seinfeld. So, since Hemingway doesn’t give his annoying guy a name, I will simply call him Kenny.

Here’s the play-by-play of how Hemingway fights against annoying people:

Hemingway is writing at his favorite cafe, getting a lot of good work done, he’s feeling good, and then he’s interrupted with a dumb question:

“Hi, Hem. What are you trying to do? Write in a cafe?”

Duh, Master of the Obvious!

Hemingway’s first tactic is to lose his temper:

“You rotten son of a bitch what are you doing in here off your filthy beat?”

and

“Listen. A bitch like you has plenty of places to go. Why do you have to come here and louse a decent cafe?”

Kenny, the interrupter, doesn’t give two figs for the insults, he continues to engage with:

“It’s a public cafe. I’ve just as much right here as you have.”

and

“I just came in to have a drink. What’s wrong with that?

Kenny has a reply for every insult that Hemingway throws at him! He won’t leave this way. All Hemingway wants is some peace as he works. Next tactic: ignore the guy.

[Kenny continues:] “All I did was speak to you.”

I went on and wrote another sentence. It dies hard when it is really going and you are into it.

“I suppose you’ve gotten so great nobody can speak to you.”

I wrote another sentence that ended the paragraph and read it over. It was still all right and I wrote the first sentence of the next paragraph.

“You never think about anyone else or that they may have problems too.”

I had heard complaining all my life. I found I could go on writing and that it was no worse than other noises, certainly better than Ezra learning to play the bassoon.

“Suppose you wanted to be a writer and felt it in every part of your body and it just wouldn’t come.”

And Kenny goes on, ‘waa waa waa I can’t write!’…but Hemingway has successfully tuned him out and it was a while before he actually hears Kenny again.

“‘We went to Greece,’ I heard him say later. I had not heard him for some time except as noise. I was ahead now and I could leave it and go on tomorrow.”

Hemingway is done writing now, so he turns back to his initial tactic insults.

[Kenny:] “Don’t you care about life and the suffering of a fellow human being?”

“Not you.”

“You’re beastly.”

“Yes.”

“I thought you could help me, Hem.”

“I’d be glad to shoot you.”

“Would you?”

“No. There’s a law against it.”

“I’d do anything for you.”

Noooo! This guy has no self esteem! This is why he won’t leave. The only true tactic in dealing with someone like this is to give them what they want–a little bit of confidence.

Hemingway does this by suggesting a new line of work for Kenny: being a literary critic.

“Do you think I could be a good critic?”

“I don’t know how good. But you could be a critic. There will always be people who will help you and you can help your own people .”

Hemingway goes on, describing all of the things the annoying guy could do as a critic, and Kenny now has a purpose and hope for some success.

“You make it sound fascinating, Hem. Thank you so much. It’s so exciting. It’s creative too.”

He is now a critic in his own eye, and Hemingway can get rid of him:

“You’ll remember about not coming here when I’m working?”

“Naturally, Hem. Of course. I’ll have my own cafe now.”

“You’re very kind.”

“I try to be,” he said.

Success! Kenny can now be avoided–at least at the cafe! That’s a start.

So, did the he become a great critic?

“It would be interesting and instructive if the young man had turned out to be a famous critic but it did not turn out that way although I had high hopes for a while.”

Ahh, poor Kenny. (91-96)

10. “I drank that bottle of wine in the dark…you were crying, I was crying. We just cried and cried…Those were the happiest days of my life, though.”

“[T]his is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy,” (211).

“[T]his is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy,” (211).

Hemingway’s last sentence in A Moveable Feast sounds much like what my parents have always said. You can hear the nostalgia in his voice, the warmth. My parents sound that way too when they look back on times when they were very poor. Once, when I was a baby, my mom and dad couldn’t afford to pay the electricity bill. That night, my mom spent all of the pennies they had stored away in a coffee can, on a bottle of wine. They always say those were the happiest times. Hemingway seemed to feel that way too.

But then we did not think ever of ourselves as poor. We did not accept it. We thought we were superior people and other people that we looked down on and rightly mistrusted were rich. It had never seemed strange to me to wear sweatshirts for underwear to keep warm. It only seemed odd to the rich. We ate well and cheaply and drank well and slept well and warm together and loved each other. (53)

Hemingway’s look-back on Paris, his poorest times spent with his wife Hadley and his new baby boy, are just filled with love. I can imagine Hemingway– successful, aged Hemingway–transcribing and editing these journals in the late ’50s and thinking ‘We really had it figured out back then.’

It makes me think that no matter what, enjoy what you have, the important things. And keep it simple. When you’re poor, that’s all you have–the simple things. What kept Hemingway going at this time was love–love of Hadley, Bumby, and his reading and writing. He had close friends and he was satisfied with a coffee or a glass of wine. He was able to enjoy what he had, not getting lost in all of the details that are so entangling when you get a bit of money.

So, if Hemingway is like all of us, let us learn from his look-back: enjoy what you have, enjoy the little things. Don’t get caught up in the race.

Sources:

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast. Scribner’s. New York: 1964.

I don’t usually enjoy reading biographies and memoirs of my favorite authors– it’s all written as a look-back; there’s a lack of tension. Plus, a lot of authors were really rotten, and I don’t want to know! However, I do really enjoy learning about some parts of the everyday lives of these god-like literary heroes. It turns out that they weren’t so different from you and me in their day-to-day habits.

I don’t usually enjoy reading biographies and memoirs of my favorite authors– it’s all written as a look-back; there’s a lack of tension. Plus, a lot of authors were really rotten, and I don’t want to know! However, I do really enjoy learning about some parts of the everyday lives of these god-like literary heroes. It turns out that they weren’t so different from you and me in their day-to-day habits.

Here are ten ways that Ernest Hemingway and other authors are remarkably similar to us!

1. They misplace their old journals!

2. They find writing to be “hard” and struggle with writer’s block.

3. They enjoy engaging in book talk with fellow readers!

4. They read fluff for enjoyment…but are wary of gambling with bad books.

5. They support indie authors!

6. They can’t afford books and hang out at the library.

7. They wish they could read their favorite books again for the first time.

8. They lose their luggage!

9. They put up with annoying people.

10. Their happiest times were when they were penniless.

*All information, quotes, and paraphrases derived from Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast, unless otherwise noted.

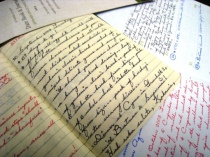

1. “Honey! Do you know where I put my draft for the Great American Memoir? I seem to have misplaced it.”

As a young writer in Paris, Hemingway regularly recorded his observations and thoughts in journals. A Moveable Feast is a compilation of these journal entries. However, the classic memoir almost never was, as Hemingway stored these journals away and later forgot about them. Luckily, his old haunt The Ritz Hotel came to his (and his readers’ rescue)!

As a young writer in Paris, Hemingway regularly recorded his observations and thoughts in journals. A Moveable Feast is a compilation of these journal entries. However, the classic memoir almost never was, as Hemingway stored these journals away and later forgot about them. Luckily, his old haunt The Ritz Hotel came to his (and his readers’ rescue)!

Hemingway’s friend and biographer A.E. Hotchner recalls their recovery in his New York Times editorial “Don’t Touch ‘A Moveable Feast'”:

In 1956, Ernest and I were having lunch at the Ritz in Paris with Charles Ritz, the hotel’s chairman, when Charley asked if Ernest was aware that a trunk of his was in the basement storage room, left there in 1930. Ernest did not remember storing the trunk but he did recall that in the 1920s Louis Vuitton had made a special trunk for him. Ernest had wondered what had become of it.

Charley had the trunk brought up to his office, and after lunch Ernest opened it. It was filled with a ragtag collection of clothes, menus, receipts, memos, hunting and fishing paraphernalia, skiing equipment, racing forms, correspondence and, on the bottom, something that elicited a joyful reaction from Ernest: “The notebooks! So that’s where they were! Enfin!”

There were two stacks of lined notebooks like the ones used by schoolchildren in Paris when he lived there in the ’20s. Ernest had filled them with his careful handwriting while sitting in his favorite café, nursing a café crème. The notebooks described the places, the people, the events of his penurious life.”

Almost immediately after their retrieval, Hemingway set about transcribing the journals into a memoir he called “my Paris book”. Unfortunately, he didn’t live to see its publication, and his fourth wife Mary Hemingway had it published in 1964. The title derived from a remembered statement that Hemingway made to Hotchner: “If you are lucky to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast,” (Hotchner).

2. Man, this writing stuff is hard!

“[Writing] was very difficult, and I did not know how I would ever write anything as long as a novel. It often took me a full morning of work to write a paragraph,” (156).

Hemingway was still very much a novice at writing fiction when he came to Paris. He had journalistic experience, but what he really wanted was to write a novel. This was a struggle, but he continued to hone his craft with short stories. He sought advice from others and set rules for himself and his writing.

When dealing with a block, he would think “Do not worry. You always have written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence you know,” (12).

3. Book Club Meeting Tonight! Bring a bottle of wine and one of your Canonical friends!

Hemingway hung out with lots of bookish types- Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and F. Scott Fitzgerald to name a few(yeah, yeah, I know “bookish” is an understatement), and oftentimes they would discuss what they were reading and would recommend books to one another. Here is some book talk between Stein and Hemingway:

“Huxley is a dead man,” Miss Stein said. “Why do you want to read a dead man? Can’t you see he is dead?”

I could not see, then, that he was a dead man and I said that his books amused me and kept me from thinking.

[…]

“Why do you read this trash? It is inflated trash, Hemingway. By a dead man.”

“I like to see what they are writing,” I said. “And it keeps my mind off doing it.”

“Who else do you read now?”

“D.H. Lawrence,” I said. “He wrote some very good short stories, one called ‘The Prussian Officer.'”

“I tried to read his novels. He’s impossible. He’s pathetic and preposterous. He writes like a sick man.”

“I liked Sons and Lovers and The White Peacock,” I said. “Maybe not that so well. I couldn’t read Women in Love.”

“If you don’t want to read what is bad, and want to read something that will hold your interest and is marvelous in its own way, you should read Marie Belloc Lowndes.”

I had never heard of her, and Miss Stein loaned me The Lodger, that marvelous story of Jack the Ripper and another about murder at a place outside Paris[…]. (26-27)

Hmmm…book recommendations from Hemingway and Gertrude Stein…I’ll take it!

4. Ugh. I don’t want to think right now. I’ll just read the latest Nicholas Sparks novel and space out, I guess.

As seen from the conversation above, Hemingway did read books simply to keep him from thinking and his mind off of writing, many of which were not considered t o be the best. Miss Stein scoffed at these reading choices, as they were simply mediocre…and they weren’t bad enough to be worth Hemingway’s time, for she espoused this notion:

o be the best. Miss Stein scoffed at these reading choices, as they were simply mediocre…and they weren’t bad enough to be worth Hemingway’s time, for she espoused this notion:

“You should only read what is truly good or what is frankly bad,” (26).

Hemingway disagreed, responding with, “I’ve been reading truly good books all winter and all last winter and I’ll read them next winter, and I don’t like frankly bad books.”

I knew I was doing something right by spending Friday nights watching movies like Plan 9 from Outerspace, The Room, and Troll 2!

5. Poor T.S. Eliot. He’ll never get the recognition he deserves…

Hemingway's pals in Paris: James Joyce and Ezra Pound in center, with two other bookish types: Ford Madox Ford and John Quinn

In Paris, Hemingway met Ezra Pound, whom he continuously described as kind and generous. Pound’s generosity was put to use in helping “poets, painters, sculptors, and prose writers that he believed in and he would help anyone whether he believed in them or not if they were in trouble,” (110). One such poet he believed in and wanted to help was T.S. Eliot, and he enlisted all of his friends to join in, including Hemingway.

“[H]e was most worried about T.S. Eliot who, Ezra told me, had to work in a bank in London and so had insufficient time and bad hours to function as a poet.”

So, Pound founded Bel Esprit with a rich American patroness of the arts, and the idea of Bel Esprit was that all of the members would contribute a portion of whatever they earned to provide a fund to get Eliot out of his day job so that he could write poetry, (111). Hemingway and other members would solicit money from friends, using the “coolness” factor to add pressure to potential donors. “Either you had Bel Esprit or you did not have it. […]If you didn’t it was too bad. […]Too bad, Mac. Keep your money. We wouldn’t touch it.”

Hemingway got into the spirit full-force: “As a member of Bel Esprit I campaigned energetically and my happiest dreams in those days were of seeing [Eliot] stride out of the bank a free man.” Fortunately for Eliot, he did get out of the bank soon after, as The Waste Land was published and won the Dial award “and not long after a lady of title backed a review for Eliot called The Criterion and Ezra and I did not have to worry about him any more,” (112). Unfortunately for Hemingway, he wasn’t the one who got to break Eliot out of the bank, and he was sorely disappointed.

The rest, as they say, is history…

Read Part Two of This Post Tomorrow!

Sources:

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast. Scribner’s. New York: 1964.

Hotchner, A.E.. “Don’t Touch ‘A Moveable Feast’.” New York Times: 19 July, 2009.

Setting is a huge part in any narrative work, be it fictional or memoir. Paris, in Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, is hugely significant– it could easily be considered the main character in this nonfiction work.

Setting is a huge part in any narrative work, be it fictional or memoir. Paris, in Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, is hugely significant– it could easily be considered the main character in this nonfiction work.

A Moveable Feast was published posthumously in 1964 and covers Hemingway’s time as a young expatriate in Paris from 1921 to 1926. As a young man in Paris, Hemingway spent his time writing, fretting over writing, and talking about books, writing, and art with his wife and circle of friends, which included Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. He also spent quite a bit of time relishing in the cafes, bookstores, and streets of Paris. For a man famed for his to-the-point style of writing, Hemingway paints a vivid picture of what it was like to be in Paris in the ’20s.

I am halfway through A Moveable Feast, and would like to share some images and a short film that illustrates the setting of Hemingway’s life in Paris. All images have been taken from the wonderful blog Hemingway’s Paris and cover the pages which I have read thus far.

Closerie des Lilas

Hemingway loved to write for hours in the cafes of Paris, and the Closerie des Lilas was a particular favorite of his. So much so, that he became very territorial if an annoying peer happened to encounter him and disrupt his writing. Here is an amusing scene when such an interruption occured at the Lilas cafe:

Hemingway loved to write for hours in the cafes of Paris, and the Closerie des Lilas was a particular favorite of his. So much so, that he became very territorial if an annoying peer happened to encounter him and disrupt his writing. Here is an amusing scene when such an interruption occured at the Lilas cafe:

“Hi, Hem. What are you trying to do? Write in a cafe?”

Your luck had run out and you shut the notebook. This was the worst thing that could happen. If you could keep your temper it would be better but I was not good at keeping mine then and said, “You rotten son of a bitch what are you doing in here off your filthy beat?”

“Don’t be insulting just because you want to act like an eccentric.”

“Take your dirty camping mouth out of here.”

“It’s a public cafe. I’ve just as much right here as you have.”

“Why don’t you go up to the Petite Chaumiere where you belong?”

“Oh dear. Don’t be so tiresome.”

Now you could get out and hope it was an accidental visit and the visitor had only come in by chance and there was not going to be an infestation. There were other good cafes to work in but they were a long walk away and this was my home cafe. It was bad to be driven out of the Closerie des Lilas. I had to make a stand or move.

Hemingway continues to insult the man, who is also a writer, and finally gets him to promise to never frequent the Closerie des Lilas again! Incidentally, this guy seems to be riding Hemingway’s coattails and reminds me of everyone’s favorite hack, Kenny Bania of Seinfeld…

Shakespeare and Company

In those days there was no money to buy books. I borrowed books from the rental library of Shakespeare and Company, which was a library and bookstore of Sylvia Beach at 12 rue de l’Odeon. On a cold windswept street, this was a warm, cheerful place with a big stove in winter, tables and shelves of books, new books in the window, and photographs on the wall of famous writers both dead and living.

Hemingway, along with many other expatriate writing greats, spent a good deal of time at this bookstore. He chatted with Ms. Beach, met with other writers, borrowed books, and even received his mail there.

Along the Seine

Across the branch of the Seine was the Ile St.-Louis with the narrow streets and the old, tall, beautiful houses, and you could go over there or you could turn left and walk along the quais with the length of the Ile St.-Louis and then Notre-Dame and Ile de la Cite opposite as you walked.

In the bookstalls along the quais you could sometimes find American books that had just been published for sale very cheap.

“Seeing Paris” in the 1920’s

This film clip was also featured on Hemingway’s Paris and offers viewers the chance to see live action of Hemingway’s Paris in the ’20s. Check it out!

This post is in response to the March prompt for A Classics Challenge, hosted by November’s Autumn